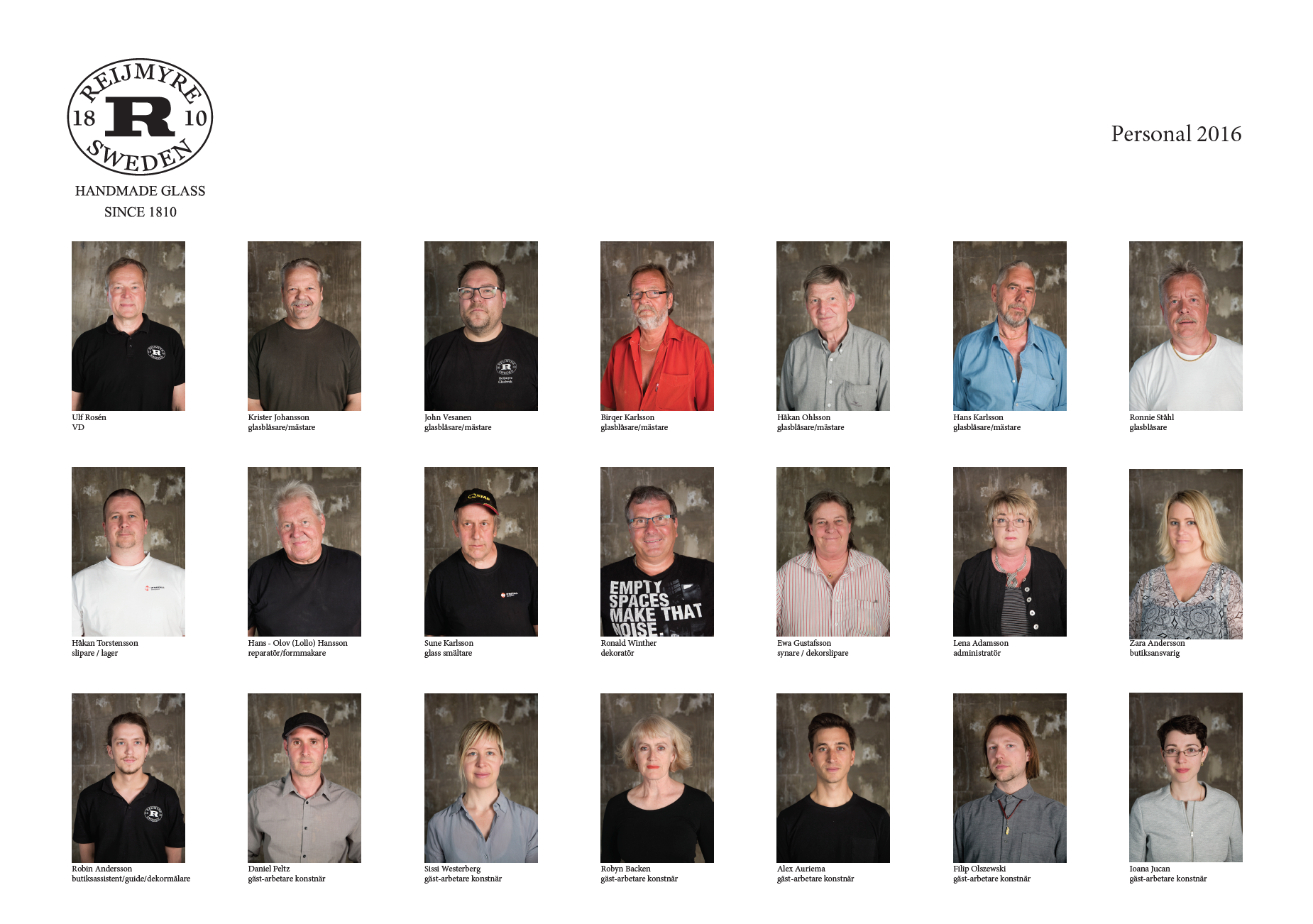

Performing labour is an artistic research project conducted in the Reijmyre Glasbruk in Östergötland from June 2016-April 2017. The project was led by Daniel Peltz, an American artist based in Sweden since 2015, and comes out of over a decade of his engagement with the town and its surroundings. The project was facilitated by the artist-run organization

Rejmyre Art LAB, founded by Peltz and the Swedish conceptual craft artist Sissi Westerberg in 2009. Performing labour enlisted a group of twelve international artists, cast in the role of researchers, including Peltz and Westerberg, in thinking labour within the Reijmyre Glasbruk. It constituted this ‘thinking' as

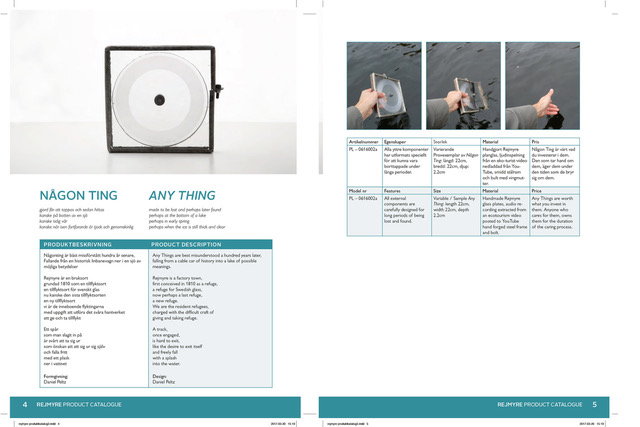

products, in the form of a product line and catalogue, and as

research outputs to be analyzed by factory workers on break and tourists visiting the factory's museum. One of its aims was to operate on/break some of the logics of research frameworks that privilege conscious knowledge and knowledge that is visible/exportable. The act of analysis within the project, usually a permission accorded to a lead researcher, is given over to two parties that Peltz refers to as ‘accidental analysts' in states of awareness that are not traditionally permissioned for research analysis, i.e. being 'on break' and 'touristing' a place. The research makes a claim for the critical epistemic validity of these marginalized states of awareness that, by virtue of being located in interstial states, resist export.

The project began with a structural intervention, the creation of a new labour category, a guest worker program, to be inhabited by artists. The artists within this program worked under a critical set of conditions:

1. being paid the same wage as the other factory workers

2. working the same hours as the other workers 6:45am-4pm

3. being subject to/part of the tourist spectacle being produced as a secondary output of the factory

Inside of this set of conditions, the artist-guest-workers worked for periods ranging from two weeks to two months and were charged with one task, to make a product of and about labour for a product line designed for two locations that Peltz has been engaged with over ten years of working at the site:

1)

the worker’s break table and

2)

the historical narrative of the factory, as presented by the historical society in their museum located inside the factory building.

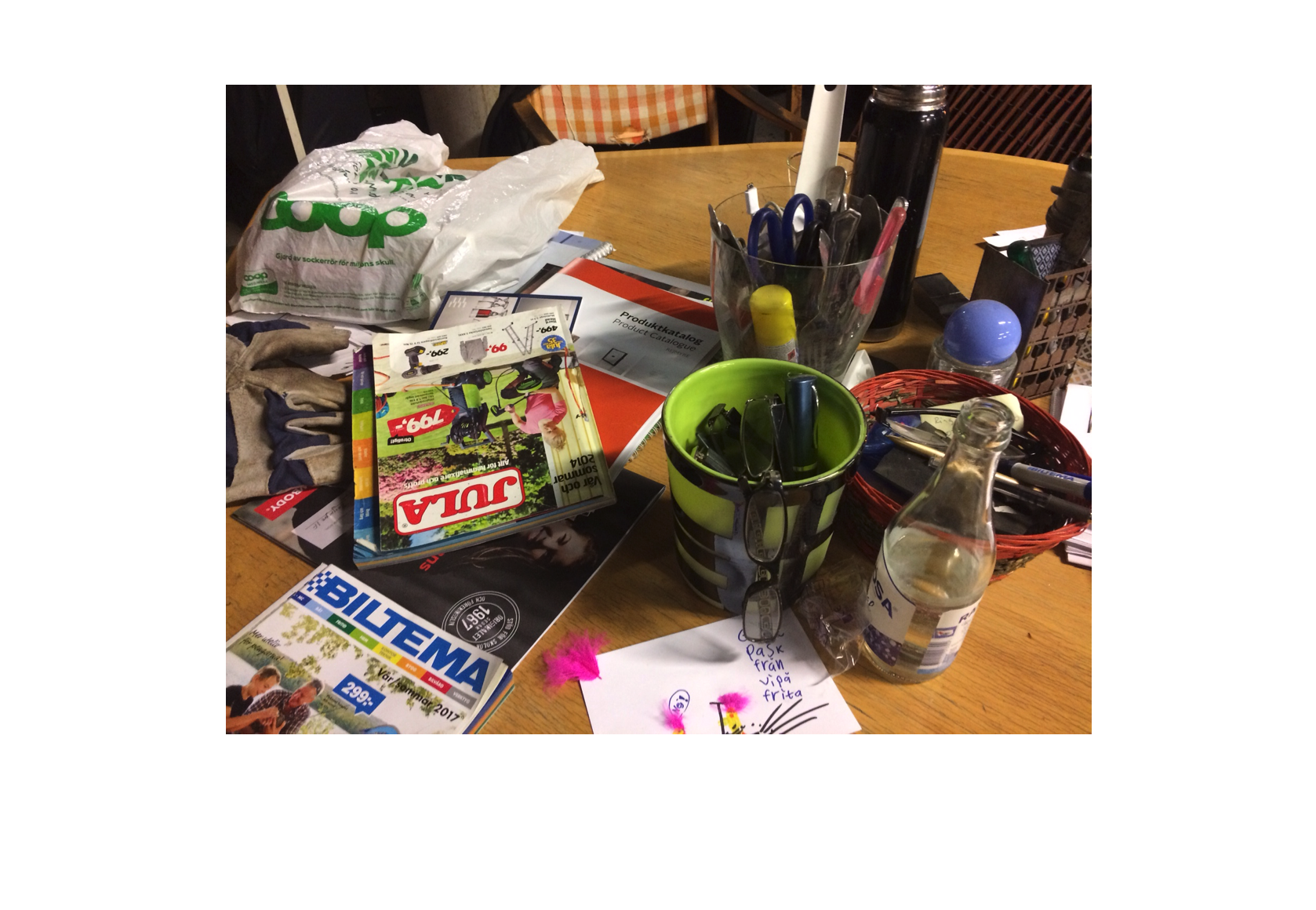

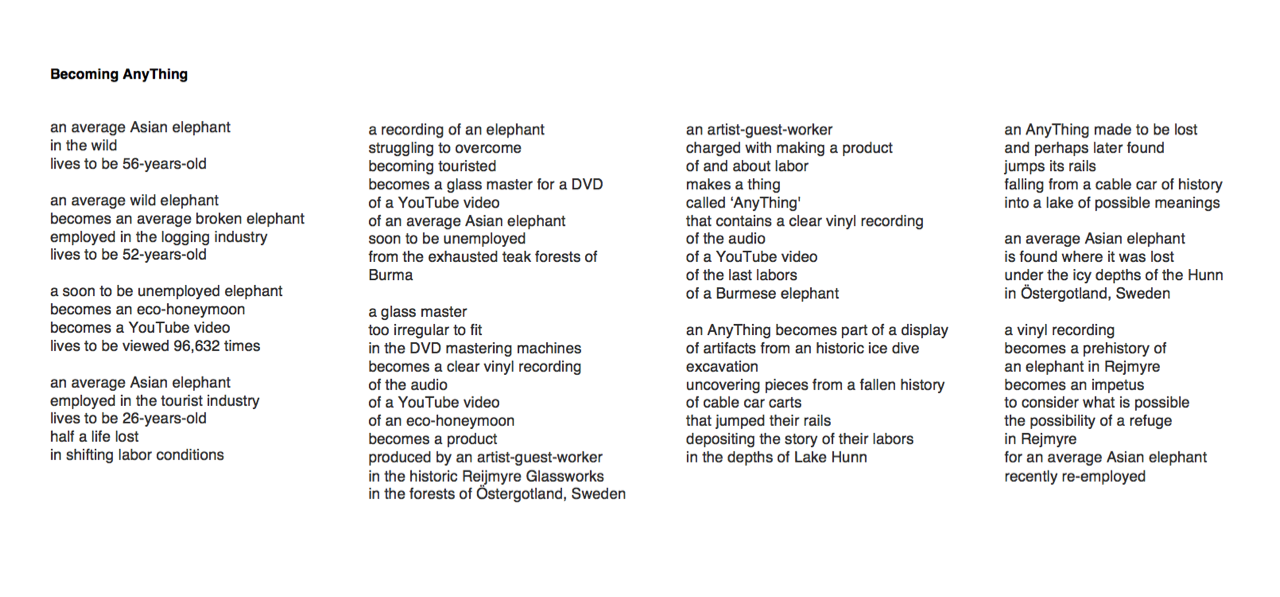

The product catalogue was designed to be inserted amongst the existing catalogues on the worker’s break table [a set of catalogues from Jula, Biltema, a supplier of pneumatic couplings and the factory's own product catalogues] that had been sitting there at least since Peltz arrived in Rejmyre in 2007] and the products themselves were inserted into the existing displays of the historical museum.

THE BREAK TABLE

PAGES FROM THE PRODUCT CATALOGUE

THE FULL PRODUCT CATALOGUE

THE PERFORMING labour PRODUCT LINE INSERTED INTO THE DISPLAYS OF THE HISTORICAL MUSEUM

___________

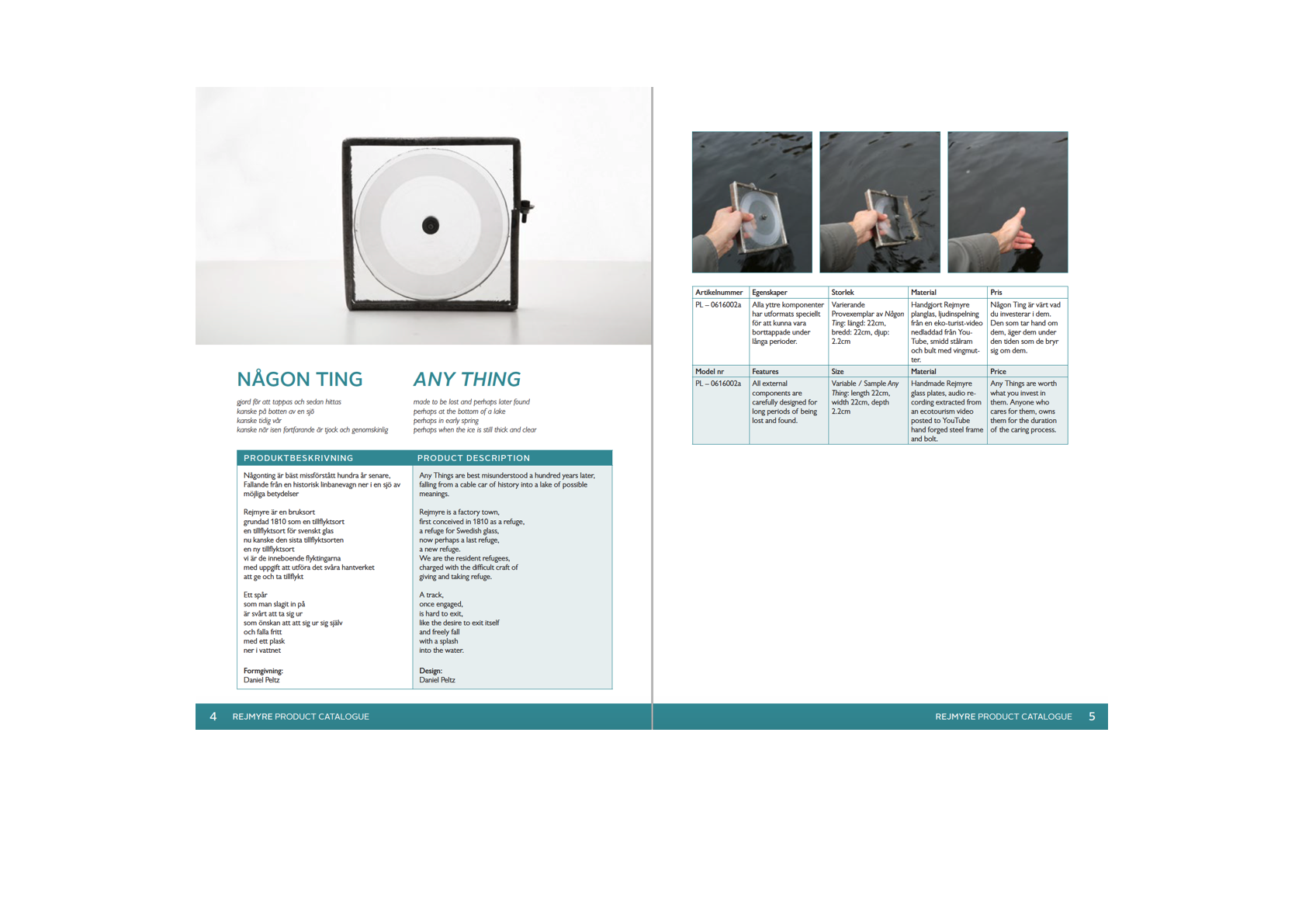

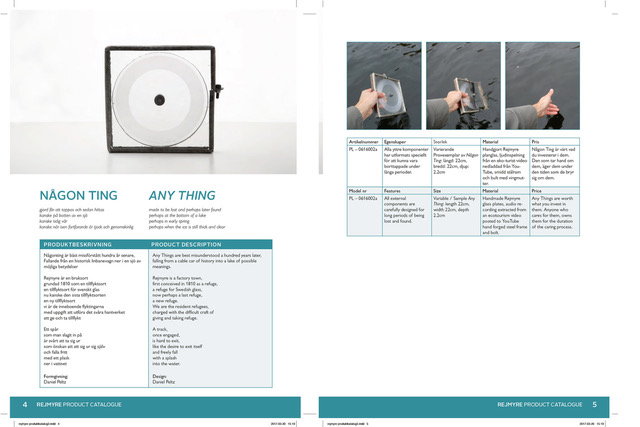

SOME NOTES ON THE ANY THING, THE REFUGE IN REJMYRE and the BUREAU OF IRRATIONAL AFFAIRS

I wrote the note below to Heinrich Hermann, the archtect and critic, in response to his questions trying to understand the Any Thing, the refuge project and the notion of Adaptive Pre-Use that I am developing within it. I include the note here as I think it provides a good introduction to the work, entering a bit more from the side than any notion of an origin:

Dear Heinrich,

I’m hoping the notes below are helpful in response to your request for clarification on the Adaptive Pre-Use model and an overview of the project.

First, to clear up a misunderstanding, the model of Adaptive Pre-Use is that of a new structure designed and built, by a specific community, for a very specific purpose that it will NEVER serve. So it is, at its core, a way of operating on the logic of adaptive-reuse, disarming its comfortable ethical and political positions and leaving us in a much murkier place, as architects, artists, residents and builders. If the logic of adaptive re-use is that re-use is ethically/ecologically preferable to ruin, or constructing with new materials, then the logic of adaptive pre-use is that building itself is, in and of itself, worthwhile, if engaged in by a specific community, in an attempt to consider the needs on an other. And perhaps the proposition is even more pointed, designing and building inhabitable physical structures, as a process of deeply considering the needs of a life, human or other-than-human, is perhaps the only way we can access some of the more subtle complexities of the contemporary human condition. By committing ourselves to this seemingly illogical project, of sincerely considering an other, and building a habitation for them, that they will never inhabit, we open a space of simultaneous possibility and impossibility that functions as a critical lens on the present and perhaps future of the human condition.

This practice is particularly resonant in Rejmyre. A factory town born in the early 1800s in response to Sweden losing its glass industry in Finland to Russia. Rejmyre became a place where people made their lives because trees, as fuel for the furnaces, and quartz, as raw material for making glass, were abundant. Like all factory towns, the needs of human lives were secondary and what was built to satisfy those needs was rarely more than a functional attempt to think a human life.

Fast forward two hundred years, Sweden is facing an influx of newly arrived people, seeking refuge from wars in their home countries. Those charged with providing ‘refuge’ to those deemed ‘refugees' encounter a housing problem, as the availability of cheap money at near zero interest rates and an existing shortage of housing stock has driven a massive increase in urban real estate values. The bureaucrats charged with solving this problem look to largely abandoned post-industrial countryside towns as a solution. In this period, a former hostel in the center of Rejmyre, a village with few opportunities for work and even fewer cultural resources, is converted into a ‘refuge' for newly arrived, unaccompanied men, many from Syria. Places like Rejmyre, that the anthropogist Anna L. Tsing refers to as capitalism’s ‘abandoned asset fields’, suddenly become temporarily valuable, precisely because the houses they contain are valueless. There was a highly circulated story in the Swedish news media, at the peak of the so called refugee crisis, of a group of newly arrived people being taken by bus to one of these rural towns that the government was reconstituting as a refuge. The story tells of the refugees refusing to get off the bus. It was a moment of concentrated disconnect between the ways in which refuge was being constituted, as an abstraction by government officials, looking to solve a problem and to simultaneously extract further value from what had been deemed a capitalist ruin, and the way refuge was being constituted and imagined by the people inhabiting this category. What was offered as a refuge was refused by the intended recipient, thus calling into question what it means to give and to take refuge? Can a refuge refused be any kind of refuge and what of those who already inhabit this place? Do they in turn become refugees? If we are going to think the complexity of this act, what it means to give and to take refuge, perhaps we need to experiment with new logics of being, Adaptive Pre-Use enters into this space.

Then you add into the mix the transformation of labour in this town built around industrial craft production that eventually turned to a hybrid version of this labour: part functional craft, part tourist spectacle. Recently, neither has been a particularly successful economic enterprise. Despite a large influx of EU money invested in remaking Rejmyre and the disused buildings of the former factory into a contemporary craft village, the spectacle of glass making in Rejmyre is losing out to other more popular destinations for consuming the image of craft production. One after another the businesses in the craft village close down: Ann’s Cafe, the bakery, the ceramic studio, the knife shop. This economic failure is accompanied by another unsuccessful attempt to construct industrial glass manufacturing as viable within the current global economy, as the high end Swedish homegoods brand Svensk Tenn attempts to extract value from the idea of the Swedish hand[made] by having their products manufactured in Rejmyre. Even this further abstraction of the glass workers' labour cannot offer a refuge from the ruthless economic logic of global manufacturing. Rejmyre is an abandoned asset field and, as Anna Tsing reminds us, there is still life here but it cannot be understood as a valuable life unless we deploy other logics.

Into this space, I begin working with an object. A thing called Any Thing, from an uncertain time, that attempts to forge a link between a group of unemployed elephants in the teak logging forests of Myanmar and this town with its own unemployment problems linked to shifting labour conditions. An article in the NY Times offers this sobering series of statistics on the life expectancy of Asian elephants:

In the wild - 56 years

In the logging industry - 52 years

In the tourist industry - 26 years

In a zoo - 12 years

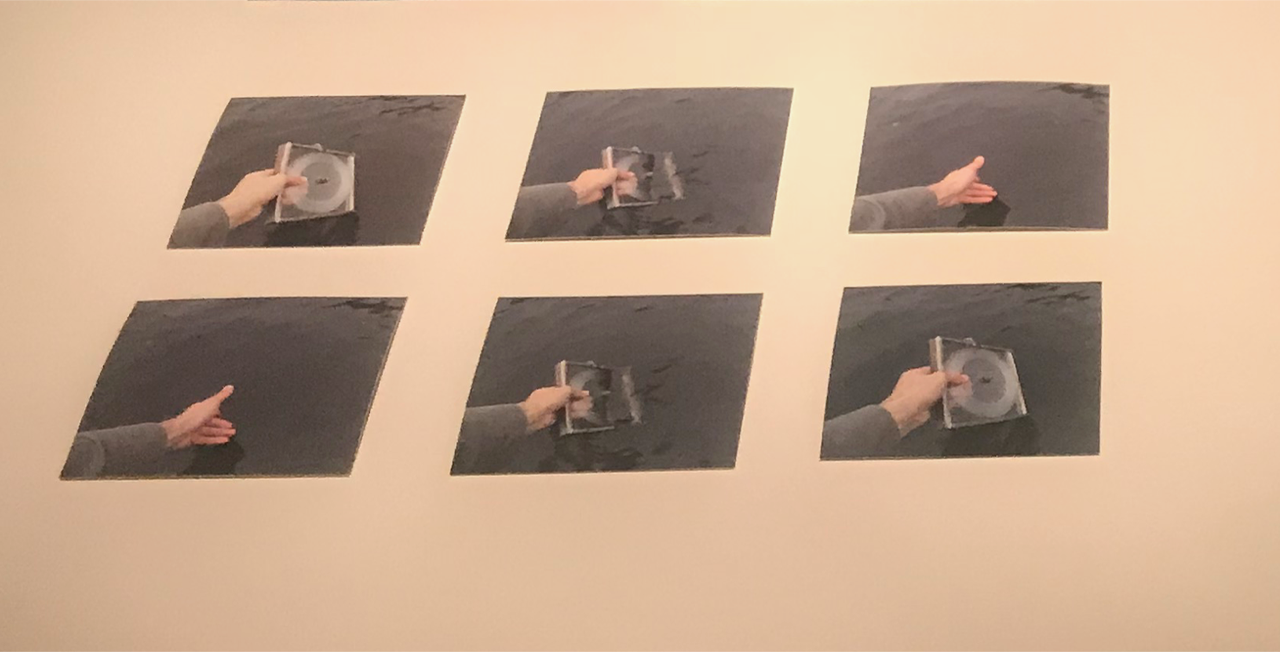

I begin to think, if we could provide refuge for these elephants, perhaps we could find clues to how to provide refuge for ourselves. How to do this? One place, it occurs to me to look, is in the historical record of Rejmyre. One way to give refuge might be to create a pre-history for the one who will attempt the more difficult task of taking refuge, such that when they arrive, they will have already been there, deep in the arsenic and lead contaminated soil mounds behind the glass factory, deep in the lakes that are fed by the stream that runs through these mounds. I make a glass and metal thing in the glass factory and the blacksmith’s forge next door, a thing called: Any Thing, made to be lost and perhaps later found, perhaps in early spring, perhaps when the ice is still thick and clear.

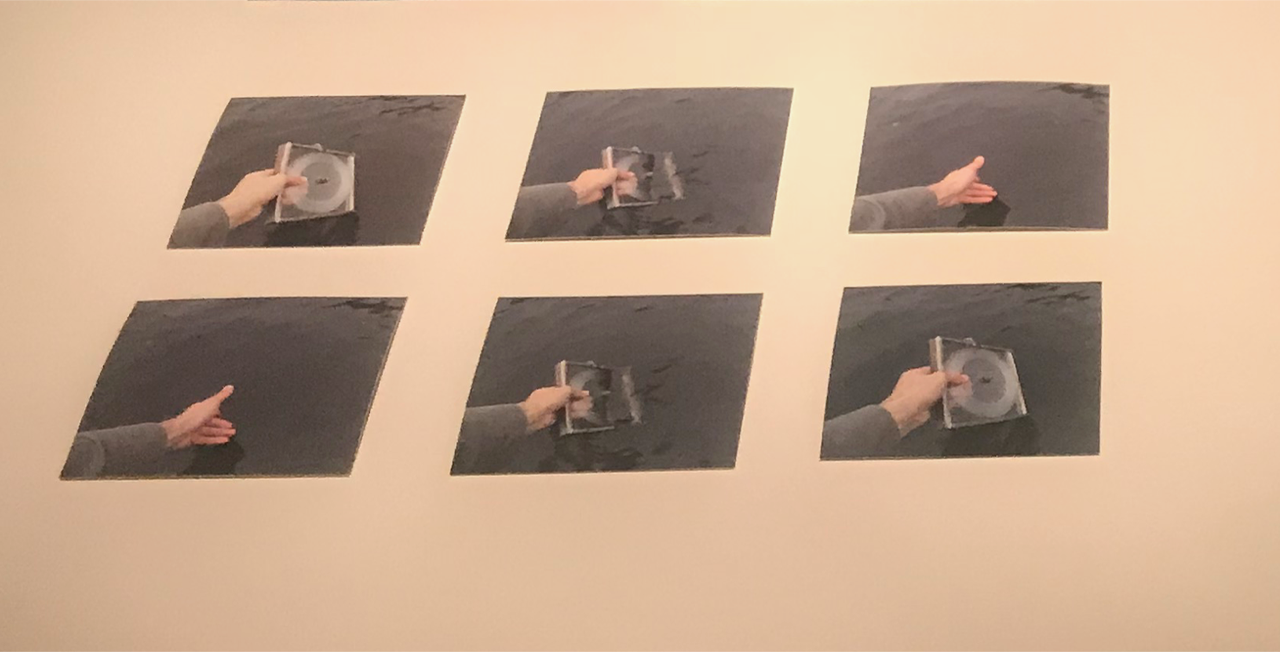

Inside the Any Thing, I embed a clear vinyl recording, extracted from an ecotourism video on YouTube of a couple on their honeymoon in Myanmar, visiting the soon to be unemployed elephants. I take this Any Thing and put it into the glass factory’s historical museum, along with a set of objects uncovered in an ice diving excavation of the nearby lake Hunn, objects that had fallen from a cable car that used to run through the region, carrying raw materials from the railway station to the factory and finished glass goods back out for export. The Any Thing sits there in the display case for a period of time. Then, I take it out, and along with a member of the historical society, I throw into the lake at the spot where the other objects in the display were uncovered.

We wait for the lake to freeze. Then, on a cold day, when the ice is thick and clear, we cut a hole in the ice, dive into the water and find the Any Thing. We open it on the ice and the sounds of the elephants’ last labours in the teak forests of Myanmar pour out over the lake to the forest beyond. This is my attempt to give and to take refuge.

The historical society agrees to acquire the Any Thing, and the video of the dive in which we recovered it, and the Any Thing winds up back in the display case in the factory’s historical museum once again.

.

With the prehistory established, the next phase involves two components that are still in motion. The formation of a new official branch of the regional government, A Bureau of Irrational Affairs, and an Adaptive Pre-use project to build a refuge in Rejmyre for a small herd of these unemployed elephants from Myanmar, to think, to imagine, to design and to build a refuge for them in this site of historic refuge for the craft of glassmaking and a contemporary refuge for a small group of newly arrived peoples.

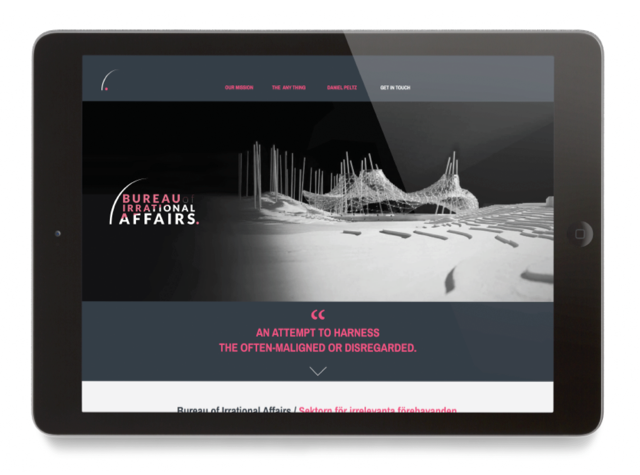

In describing the bureau I write:

Bureau of Irrational Affairs / Sektorn för irrelevanta förehavanden

Logic and rationality are often unquestioned values in the ideology of government, yet the forces that govern our internal and external lives contain significant irrational and illogical components. The Bureau of Irrational Affairs challenges the fundamental structure of government, making an official space for artist‐driven proposals and programs that operate beyond the rational sphere. In doing so, the bureau attempts to address disenfranchised aspects of public consciousness and expands the ‘vocal range of bureaucracy'. It is partly concerned with what 'irrational government' can do for the 'irrationally governed' but equally concerned with the ‘ungovernable' aspects of those charged with the task of governing.

The projects proposed within the bureau will be pursued with interdisciplinary depth, diligence and sincerity. In a time of catastrophic ecological crisis, unfathomable economic inequalities and radical alterations to social and somatic modes, the implementation of a Bureau of Irrational Affairs could well constitute a deeply sensible way of creating the conditions for the emergence of relevant public policy.

Recent efforts to involve artists in bureaucracy have often inadvertently instrumentalized artistic practice in the service of public agendas and limited their more subtle potentials. The Bureau of Irrational Affairs differentiates itself by declaring the need and right to address ‘irrational affairs’ in an official autonomous capacity, making a claim for artists’ capacity to function as fully-qualified bureaucrats. The bureau attempts to reframe public understanding of how and what contemporary artists do and to harness the skills and modes artists are being trained in: complex, open, materially responsive, multidisciplinary, research‐based practice.

The conceptual construction of the bureau is fundamentally divergent from the conceptual construction of most bureaucratic efforts and agencies. It attempts to harness the often maligned, or disregarded, powers of that which exceeds the bounds of logic and rational thinking. This holds the potential to break new ground in thinking about the role and function of government, the scope of what it can address in its current form and what ways of being and communicating we allow government employees and government communications to take on. Part of the argument for this structural experimentation, with new forms of government, is that the complexity of contemporary existence is unable to be addressed by the current forms and modes of being. The establishment of a bureau of irrational affairs speaks, in a playful, critical and engaged manner, to the challenges of an increasingly culturally heterogeneous Sweden, that must rethink its very notion of government and the supposedly universal logics that underpin its rules and regulations.

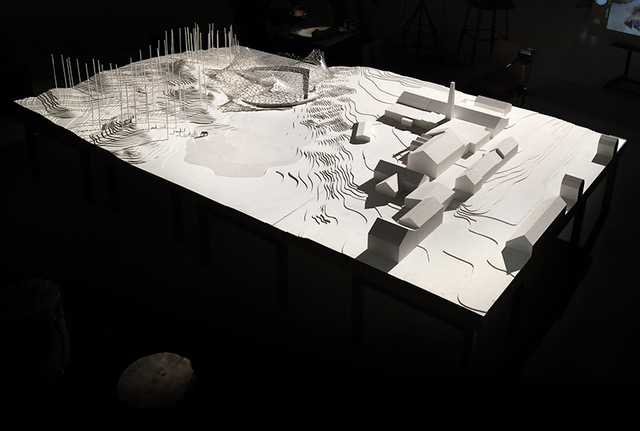

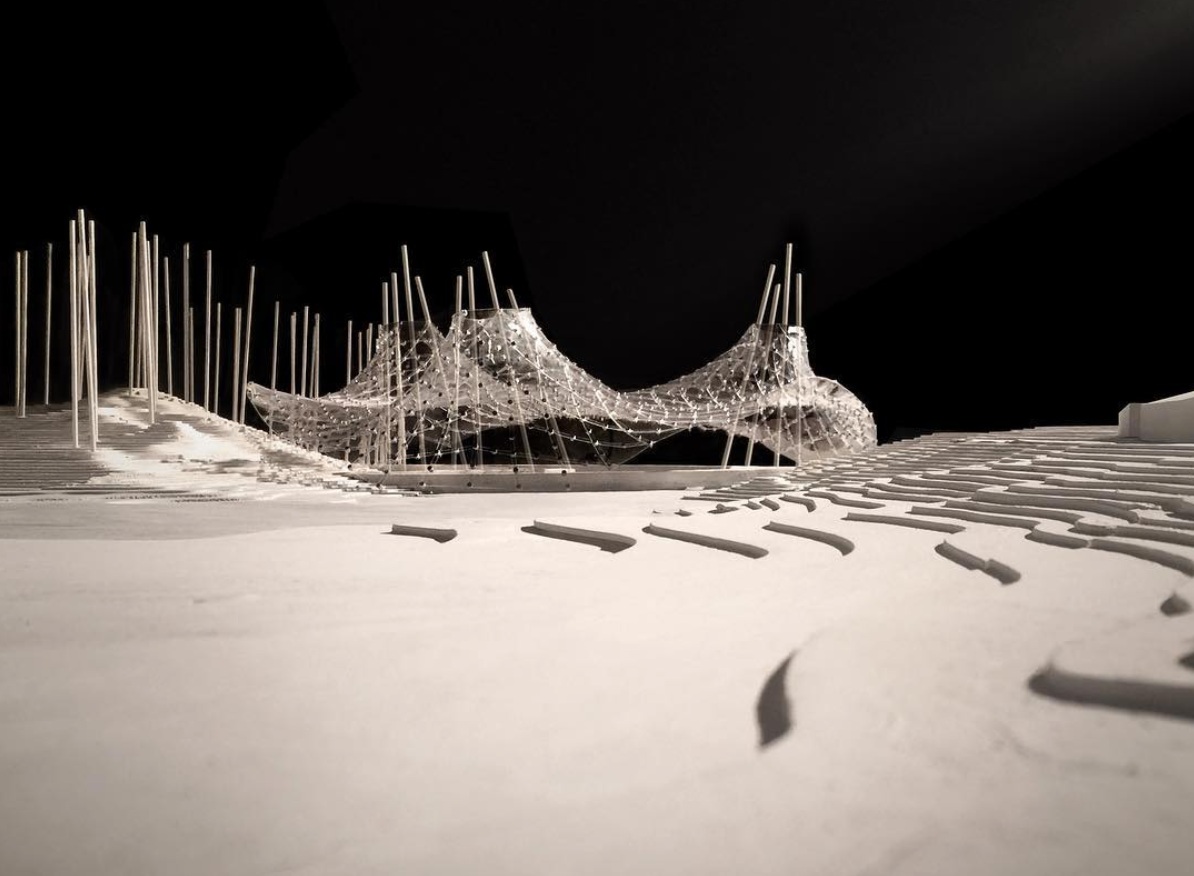

The first project of the bureau is the building of a refuge in Rejmyre. I contact Kristoffer after being invited to do something inside his Dome of Visions while working as a guest professor in Stockholm. A structure built on the campus of the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm, designed to be virtually connected to a similar structure in Copenhagen.:

Stockholm Dome of Visions

Copenhagen Dome of Visions

I wondered what would happen if we transposed the logic of connecting existing capitalist power centers like Copenhagen and Stockholm onto an 'abandoned asset field’ like Rejmyre. I invited Kristoffer to come visit me in Rejmyre and we forged a bond that has led him to agree to develop an initial design for the refuge, for a refuge in Rejmyre, to be imagined, redesigned and built by residents as an attempt to ask and perhaps, in the act of building, answer, the question: ‘How might we give and take refuge, for our perilous selves and perilous others, in this abandoned place in which life still resides?'

He begins by consulting with an expert, a woman who wrote her PhD on working elephants and consulted on the development of the Foster and Partners elephant house in Copenhagen. We take what we learn from her and what we learn from exploring the site around the factory and Kristoffer’s initial proposal for a structure, built by local skilled volunteers, to house a small herd of unemployed logging elephants from Myanmar, takes shape. This proposal will be presented at the exhibition in April at the Norrköping Art Museum and serve as a platform to gather residents around, deploying the power of the art institution and the power of the architectural model, to hopefully allow enough people to take this forward to the next stage, to imagine, to redesign and to build this refuge with us.

I thought I would close this text with a poem I wrote to accompany the project in recent presentations and that will appear on the wall in the exhibition in Norrköping:

__________________

Break Blowers - Sissi Westerberg

Sissi’s installation builds on her Break blower product. It is a pneumatic sculpture that activates during the glass blower’s breaks.

A short description in Swedish and a video of the piece installed in the factory can be seen here:

Pausblås (2017) är en tryckluftsdriven installation av Sissi Westerberg som utvecklats från projektet Perfroming Labour. Verket bestod av glasobjekt skapade på glasbruket med uppblåsbara latex delar. Verket drevs av den befintliga tryckluften i glashyttan och reglerades med pneumatiska ventiler, pausrelän, och en timer som var programmerade enligt arbetarnas rast-schema. När glasblåsarna går parastatals arkiveras verket och pausblåsarna börjar andas/blåsa. I utställningen flyttas installationen med pausblåsarna och viss rekvisita från glasbruket in i galleriet. Videon som dokumenterar verket i glashyttan visas som en projektion

___________________

There Was Nothing Else to Do with the Forest - David Larsson

____________________

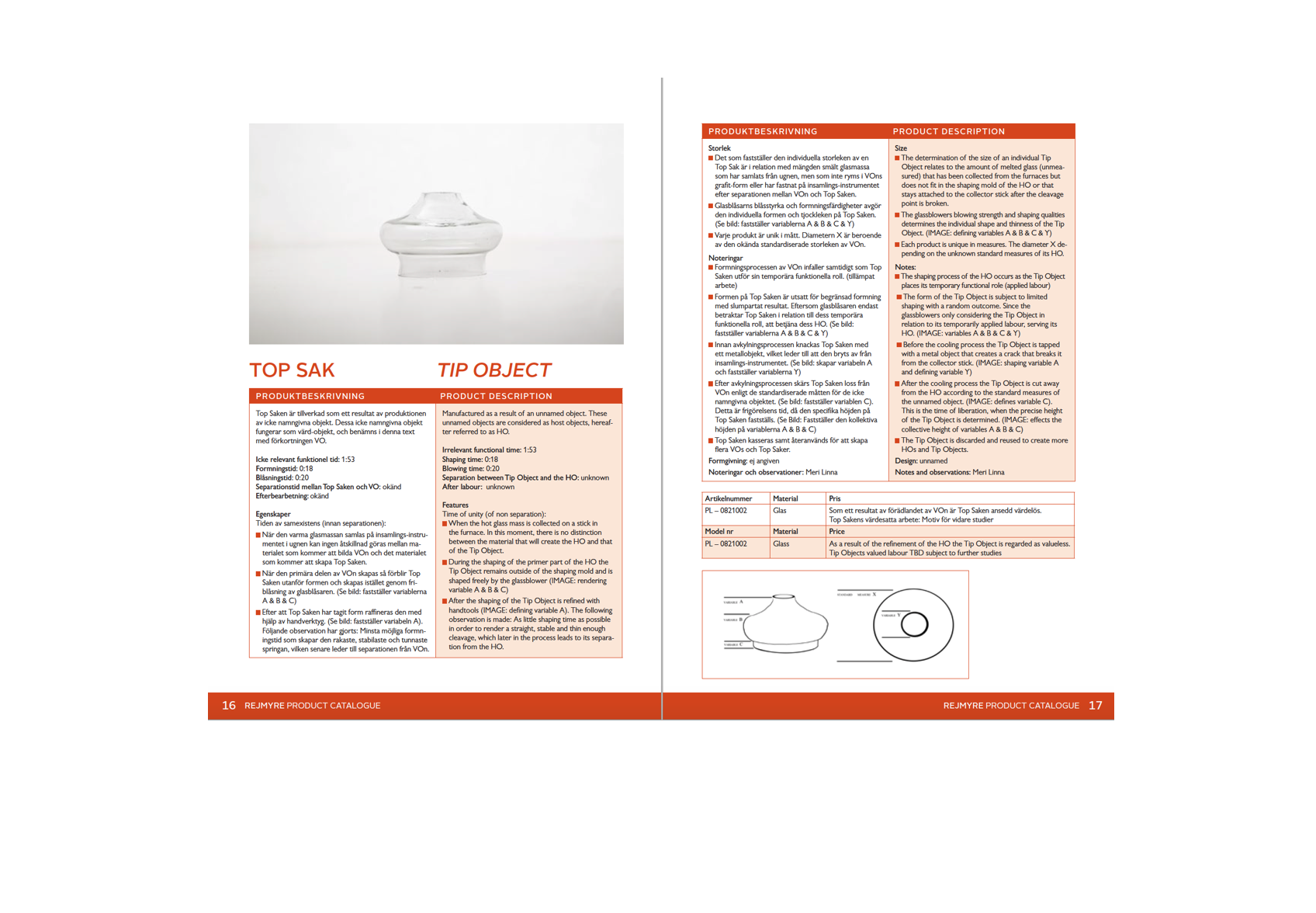

Meri Lina’s work Tip Object is unchanged from the Product Catalogue but is installed as a for-sale item in the museum gift shop.

Hoping this helps and looking forward to your questions,

Daniel